What Was, What Wasn't

Michael Adno

The Spanish imagined Florida as an eternal elixir. The French searched here for spiritual freedom. The British fashioned it as an instrument to build an empire. Tribes on either side of the State’s liquid heart deemed it sacred. Slaves in colonies further north escaped by reaching this borderland, while slave traders used it as a backdoor into America. Florida became a republic, a territory, and then a State. But always, it remained a collection of myths and contradictions, constantly reinventing itself through the outcasts who preferred the sub tropics. The peninsula falls south from dense pine forests into scrub and sedge before dissolving between the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico in a string of coral. It was once a bellwether for the nation, yet it belonged more to the tropics and Latin America than it did the United States. Americans from the mid-west and the mid-Atlantic ran down Interstates 95 and 75 to build along its coasts like mangroves. Cowboys and carnies made lives here. Criminals and politicians resurrected themselves. Some decided national elections and even redrew the electoral map of the country here. It animated serious works of literature, served as a honeymoon for Walker Evans, but the place changed as quickly as the storms that formed along its edges. For my family, Florida was home, due to a man hiding in the woods.

In 1938, my grandfather, a Viennese Jew, fled Vienna on a train bound for Switzerland. Near the border, the Schultzstafel boarded the train, and my grandfather slipped through a window before he disappeared into the forest. But when the train continued, he saw another man crouched behind a tree and introduced himself. Soon after, the two split up before crossing the Rhine River, and my grandfather escaped Europe, spending the war in the Dominican Republic. But when he returned to Vienna, he met that man from the woods again, and many years later once my parents had moved to New York City, they went with my grandfather to visit that man in Florida where he now lived. They fell in love with Florida, left New York, and that’s how I ended up here. My parents, who were from Austria and South Africa, bore no ties to Florida let alone America, so the idea of home became as complicated as the place I grew up, toggling between Sarasota, Vienna, and Johannesburg where my family still lived. In Sarasota, they taught us to outrun alligators as kids. There were punks and skaters, soon-to-be frat boys and country club athletes. Your jeans and shoes placed you. We built bike trails out of dirt, skateparks in stands of trees, and that’s where we learned to smoke and drink around town. At night, the eclectic patchwork of kids gathered in the same woods, chasing a keg from remote fields to house shows. Some grew up and left. Some stayed and disappeared. Once I left, I was often asked about Florida. I wasn’t sure what to say. The more I thought about home the more mysterious it grew.

For a while, I tried to persuade those who asked to accept something beyond what was in the headlines. I explained how Florida was made up of regions that were so culturally, ecologically, and historically distinct that any singular understanding contradicted others. I told them how we performed our histories in beautiful ways while ignoring other less marketable histories. I tried to explain how our sense of place formed through family and our distance from them, through the sum of our friends, and whether you knew the names of trees and when they flowered. I thought otherwise. After college, I became a writer and had the chance to spend thousands of hours writing about the place. Finally, I let go of understanding Florida, and I began to make these photographs. I was spellbound by my home, and I wanted to record a little of what lent it its character, especially since so much of its charm vanished as it grew. What I ended up with was a clear sense of what makes a home ultimately a home, the good and the bad, the people and their past along with mine. That pursuit became a simple but powerful act of looking at a seemingly flat place and finding a deep well of curiosity. It became a celebration, too, of the complicated, ever-changing State and a warm embrace of the people who call it home. I guess I hadn’t really given up on understanding the place, because my fascination only grew deeper. My crude form of myth making then turned into a love-letter to home.

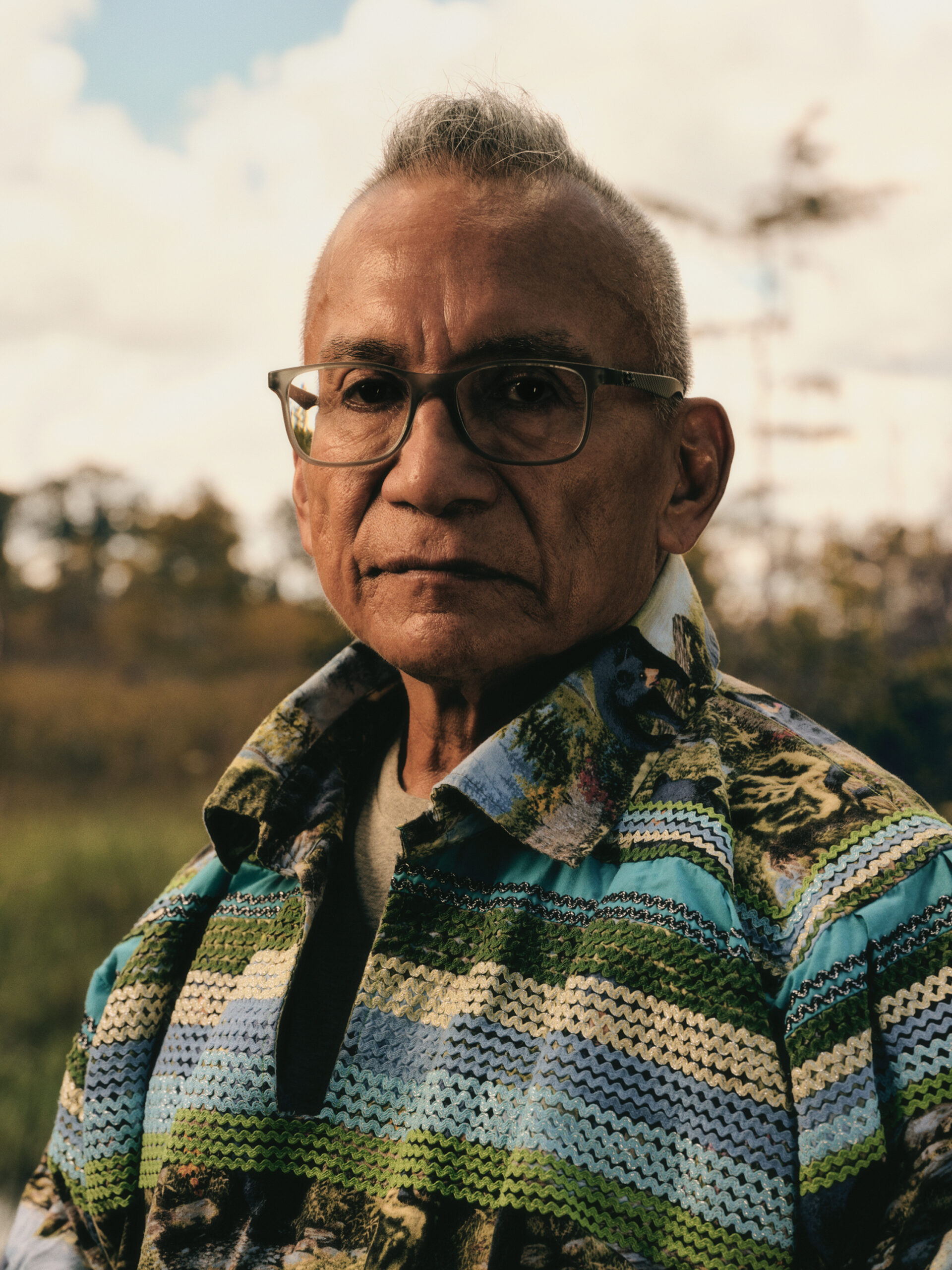

Michael Adno (b. 1990) is a writer and photographer living in Sarasota, Florida. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the New Yorker, and the Bitter Southerner among other magazines. He won a James Beard Award for his profile of Ernest Mickler, the author of White Trash Cooking. His writing has won three Green Eyeshade Awards in business reporting, feature writing, and environmental reporting. His story for the Oxford American about a couple who make their living conjuring worms out of the ground will be included in this year’s Best American Science and Nature Writing, edited by Susan Orlean. In 2025, he began writing his first book, The Stranger in Our House, a family saga about how a traumatic brain injury reshaped their lives. Adno graduated from New York University before attending residencies at the Hermitage, the Key West Literary Seminar, and the Lower Eastside Printshop. His work has been supported by fellowships from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Foundation, the Julia Child Foundation, and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Michael Adno